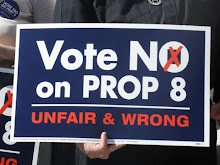

On April 13th a not-so-anonymous Jon (Book of Revelation reference, anyone?) posed a number of formidable questions about the definitions of marriage, and opined that marriage is, “for all of the history of the word has been a contract between a man and woman.” This entry will be devoted to the refutation of his argument in the interest of civil discourse.

Jon’s argument focuses on two main arguments: (1) the definition of marriage is historically and linguistically defined between and man and women (2) if same-sex couples would like to be “married” they simply need a “new word”. When Jon initially posed his question, my etymological knowledge of the word marriage was fairly weak. Not one to be easily discouraged, I decided to do some research and see what I came up with. Now, as I already knew my stance on the issue of gay marriage, I was hoping to find that marriage meant nothing more than “union” in its linguistic derivation. As my search moved out of its nascent stages I began to question whether researching the semantics surrounding a word had any real place in the Prop 8 debate. You might be expecting me to parry Jon’s arguments by taking such a route, but Jon accurately aimed his critique: that is exactly what Prop 8 is about – semantics.

Legal definitions are debated down to their etymological core in the interest of accuracy and situational resilience. That being said, my research yielded varying results. This variance, I propose, is due to the different purposes of definition types (1) Legal definitions, (2) etymological definitions, (3) Contemporary or “common use” definitions, and (4) Academic definitions. All of these definition types host a wide gambit of explanations on the meaning of marriage, but no category ubiquitously claimed this union was between a man and a women. Interestingly, academic and contemporary definitions tended to favor the “man-women” definition, while legal and etymological definitions favored a broader defined union. Unfortunately for Jon’s argument, he placed an etymological idea inside a legal construct (the same rational posed behind the Prop 8 bill).

Etymologically speaking, it's a stretch for marriage to mean anything more than joining or union, and this union is not necessarily a union of two. The term “gam” is a root that means marriage. This root can be found in words such as monogamy, polygamy, autogamy, bigamy, exogamy…. Get the idea? Based on this information it’s difficult to postulate that marriage remains a word linguistically grounded in male-female connotations. What you could argue is that society has commonly referred to marriage as male-female. This assertion, however, will only go as far to suggest that this is the dominant representation of the word, and on that note we are all in agreement. Applying this formula in practice, to use reductio ad absurdum, would be akin to deeming the University of Minnesota, by linguistic definition, a white school because it has historically been dominated by that race. Since same-sex couples seem just fine with using the word marriage, might I suggest straight couples find a neologism to describe their union if they are unwilling to share the word marriage with everyone.

Jon’s argument focuses on two main arguments: (1) the definition of marriage is historically and linguistically defined between and man and women (2) if same-sex couples would like to be “married” they simply need a “new word”. When Jon initially posed his question, my etymological knowledge of the word marriage was fairly weak. Not one to be easily discouraged, I decided to do some research and see what I came up with. Now, as I already knew my stance on the issue of gay marriage, I was hoping to find that marriage meant nothing more than “union” in its linguistic derivation. As my search moved out of its nascent stages I began to question whether researching the semantics surrounding a word had any real place in the Prop 8 debate. You might be expecting me to parry Jon’s arguments by taking such a route, but Jon accurately aimed his critique: that is exactly what Prop 8 is about – semantics.

Legal definitions are debated down to their etymological core in the interest of accuracy and situational resilience. That being said, my research yielded varying results. This variance, I propose, is due to the different purposes of definition types (1) Legal definitions, (2) etymological definitions, (3) Contemporary or “common use” definitions, and (4) Academic definitions. All of these definition types host a wide gambit of explanations on the meaning of marriage, but no category ubiquitously claimed this union was between a man and a women. Interestingly, academic and contemporary definitions tended to favor the “man-women” definition, while legal and etymological definitions favored a broader defined union. Unfortunately for Jon’s argument, he placed an etymological idea inside a legal construct (the same rational posed behind the Prop 8 bill).

Etymologically speaking, it's a stretch for marriage to mean anything more than joining or union, and this union is not necessarily a union of two. The term “gam” is a root that means marriage. This root can be found in words such as monogamy, polygamy, autogamy, bigamy, exogamy…. Get the idea? Based on this information it’s difficult to postulate that marriage remains a word linguistically grounded in male-female connotations. What you could argue is that society has commonly referred to marriage as male-female. This assertion, however, will only go as far to suggest that this is the dominant representation of the word, and on that note we are all in agreement. Applying this formula in practice, to use reductio ad absurdum, would be akin to deeming the University of Minnesota, by linguistic definition, a white school because it has historically been dominated by that race. Since same-sex couples seem just fine with using the word marriage, might I suggest straight couples find a neologism to describe their union if they are unwilling to share the word marriage with everyone.

It's tough to find out how to argue a question of semantics. Should we go around looking for common practice in the use of the word or should we argue for how the word ought to be used? It seems the research would say that their is at least some lack of clarity in the formally created definitions. I contest here that the clarity is not lacking in almost every single instance of the words' usage. Over history this word has been between a man and a woman without question to almost every person. Only recently has it changed to have people thinking, 'well, could we let the other sorts of sexual people use this word too?'

ReplyDeleteMy point ends in that the burden of argument is in the homo-sexuals' court. They would like a word modified to accommodate peoples' best interests. I don't need a reason why they can't, but they need a reason why they ought to. In modifying language to better serve the world, one must explain why the world will be a better place under the new usage. Frankly, I don't see that case being made. I just see a hole lot of, 'well why not let them come to the party?' But I don't think it is just the nice thing to do to make a stand against a word based upon thousands of years of practice. Where is the faith in the language we have?